Click here to read something about who I am and what motivates me.

Click here to download this as a PDF file.

What follows are extracts from a book that will be published when I find time. I have tried to avoid naming names unless I have something positive to say (but have not always succeeded). If I have named you and you would rather I did not, let me know and I will remove your name.

The Humanitarian Demining (HD) days

I got involved in demining in 1994 while working as a (mostly volunteer) technician and scribe for a development charity based in the engineering department of the University of Warwick in England. The charity worked on developing appropriate technology for transfer to developing countries and I had spent several years with them working on low-tech rural water supply systems. Unlike most people starting in demining, I was already over forty and not looking for a career. After a trip to Mozambique to look at the demining being conducted in Maputo Province, I wrote a paper in which I identified three needs which the 'appropriate technology' charity could try to address. These were, 1) face and eye protection, 2) blast resistant hand tools, and 3) a small machine to cut undergrowth in advance of the deminers.

I contacted the two British demining charities, Mines Advisory Group (MAG) and HALO Trust, speaking to Rae McGrath for MAG and the late Colin Mitchell for HALO. Rae came and gave the University group an introduction - showing a range of mines - and Colin spent a couple of hours being charmingly rude as he emphasised the need to get out and be a deminer myself (Colin had charisma, which excused a lot). Both were surprisingly patient and helpful. Colin advised that I should talk to the actual deminers, not the 'experts' in charge, and get the deminers to teach me what they did. This has worked and while I have rarely shared a language with the deminers, they have taught me their methods and then let me show them the way that others work. Inspired by Rae and Colin but still woefully ignorant about the blast forces involved with high explosives, I made a range of equipment which I then blast tested with the British 'Territorial Army' on Salisbury Plain (introduced by retired Brigadier John Hooper).

My early work on body armour is described in the first parts of this page.

My early work on visors and face protection is covered in the first parts of this page.

My work on safer hand tools is covered on this page.

My work with area preparation machines is covered here.

It is not necessary to visit those links to understanding the following, but it may help.

After my first blast tests, the University group were offered two days of training by the British army at Minley Manor. This training was limited to lying shoulder to shoulder prodding the ground with bayonets and playing soldier "spot-the-tripwire" games. David Hewitson (ex-HALO Trust) turned up to tell us this was not relevant to humanitarian demining. He was a submariner so the army tried to dismiss him - but that was water off a diver's back. Thank you David Hewitson. The training was a good introduction to the way that military demining differs from humanitarian demining and a preparation for the ignorance of those ex-army 'experts' who frequently fail to appreciate that difference.

I was listening and trying to learn from the people in charge while I developed designs of cheap and practical personal protective equipment (PPE). But I also spent time in the field with the actual deminers in Afghanistan, Cambodia, Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Namibia, learning what they really did, trying it myself, and realising how little those in charge knew about the work on the ground. What I learned included the fact that there wasn't one way to do the work and that there were no two 'experts' who agreed on anything from the varied effects of different types of High Explosive to the use of a metal-detector and the need for Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Most had no idea how the hazards we were finding worked and saw no need to find out. I started to take mines apart to collect their metal content in order to test metal-detectors and got involved in proving that the old Schiebel AN19 detector (then used by the US Army so favoured by the UN) was incapable of finding many of the mines. This meant gathering enough evidence to convince people who already knew everything - and it took years to enlighten them. Fortunately the internet was starting to blossom and those of us who cared could start to pool real sources of information and experience despite being continents apart. This made us harder to ignore.

While designing and making PPE, I worked as a surveyor and deminer in rural Mozambique, disarmed and destroyed mines, and started to have the confidence to ask awkward questions on an internet forum that had become very influential in demining circles. I learned that the tools and equipment we were expected to use were often incapable of doing the job, that demining was an uncontrolled black hole into which donors threw money (a goldmine for amoral mercenaries) - and that it was easy to embarrass those who had assumed power. Naively, I believed they would want to know when things were not right but I was wrong. Lost in the idealism of the run up to the millennium, it really did not occur to me that some were doing their best but working to an entirely different agenda that usually involved paying mortgages and expensive ex-wives and often involved doing as little work as possible. Most were also ex-military and having been through "the best training in the world" they obviously had nothing to learn from a civilian.

There are not many photos of me from that pre-digital time because I was usually holding the camera. These show me as a researcher in Mozambique in 1994 and as a deminer using a watercourse to cross the border minefield in 1996 - a rather hot adventure.

The University of Warwick denied all knowledge of me when I blew the whistle on a scam involving "clearance" of an area with no mines in Mozambique. I was a contractor rather than an employee and the University wanted no trouble. The scam was embarrassing my deminer friends who had been told to pretend to search and then to detonate some plastic explosive occasionally, so making it look as if they were finding mines. I was with the late Keith Byng of ROMTECH at the time and we were obliged to border-hop across the minefield out of Mozambique when the dodgy commercial company was told that I had no connection with a UK University so their owner thought it safe to put a $1000 price on our heads. That's a story involving sacks of skulls in a Harare suburb and the loyalty of black friends in a time of white cowboys. I lived on because my would be nemesis, known as Bernie, was notoriously reluctant to ever pay out. The deminers laughed and told me that no one would shoot me without having the money up front. The boss of another commercial demining company based in Zimbabwe did not want bad publicity so put pressure on Bernie to lift the contract. So instead of killing me, Bernie, then owner of a company called Special Clearance Services, met me in a Harare bar where he bought me a beer and offered me a job, which I declined. Funny old world.

Feeling unjustly abandoned, I parted company with Warwick University, who had never been able to pay me anyway. I got some independent funding from a small medical charity to keep on with my PPE work (after successfully arguing that preventing injury fell under their medical remit). I later heard that I had left Warwick University under a cloud after stealing a FAX machine. The Warwick group had carried on with their attempts at making visors and the ill conceived Tempest machine (ill-conceived by me, I admit) that I had started in Cambodia. When they were asked why I was no longer involved they told people that I had stolen a FAX machine and I suppose that probably seemed as good a lie as any other. Hey, I had no engineering qualification anyway so I was no loss to their group. With some sense of irony, I have since accepted several formal invitations to give talks to Warwick University's postgraduate engineers and only stopped going because they never got around to paying my mileage. They think that I must have a secret income - well, how else could I do so many things unpaid? I didn't have any other income but I did have a partner with a job and we always got by.

Having an internet presence led to me being invited to speak at the signing of the Ottawa Convention (Mine Ban Treaty) in Canada, not in the main hall, but at a packed side event chaired by the Italian government minister Emma Bonino. I had never spoken from a platform before and I was to be the first up. Sitting at a table on a raised platform in front of a lot of people, I was obviously nervous. Emma Bonino was sitting at my side. She smiled at me as she did the introduction, then placed a comforting hand on my thigh. The audience could see her hand, saw my jaw drop, and they laughed. That worked - and I read my paper better than I might have done. Thank you Emma Bonino.

My paper was titled "There are no deminers at this conference", making the argument that the people who are on their knees all day were not represented and their needs should be remembered. It was not a bad paper, considering my inexperience. Bob Keeley (now Dr Bob) was in the audience and he resented the implication that he was not a deminer, so bobbed up to say that he was. He was an Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) callout man in Cambodia, so closer to a deminer than some, but he had not listened to a word and there was an embarrassed silence. Not embarrassing for Bob, but for everyone else. Our paths have crossed from time to time over subsequent years, and Bob has usually lectured me about my diplomatic failings. I suspect that he may be a good man, albeit heavily disguised.

I was trying to find a donor or partner to help me repeat my PPE work locally in Afghanistan, or inside Pakistan to supply Afghanistan, and a Professor from the University of Western Australia expressed interest. His father-in-law had a research centre in Pakistan so I went out to Islamabad to try to teach them how to make visors and body armour. The Hammeed and Ali Research Centre was actually a "relaxation centre" at the back of an urban house where nothing happened, and that very slowly. Frustrating, but I got back into Afghanistan and travelled around with the deminers, did a few blast and fragmentation tests on armour I had made on the street in Rawalpindi, watching, and learning.

Listening to Mansfield or Bullpit (successive Chief Technical Advisors for what was then called the UN Mine Action Coordination Centre for Afghanistan - UNMACCA) you would think that Afghan deminers lay flat to prod for mines with bayonets but they only did that for the UN's photographers. It was too hot and dirty to lie down, very unsafe to lie down to prod for mines, and no one can work while lying prone anyway. The idea of demining while lying down originates in military training when soldiers are obliged to present a smaller target to anyone shooting at them. The myth that you can demine with your chest against the ground has been perpetuated by many blinkered senior managers who have a military background and manicured hands. Bullpit and Mansfield were not even based inside Afghanistan - but in comfortable Islamabad in Pakistan - and their field experience was limited to superficial minefield tourism. At that time, the same senior managers were often insisting that deminers work in three man teams, one detecting, one digging up the mines, and one standing guard over the other two. Of course there is no need to have a guard in humanitarian demining which is only done when the combatants all agree to it. But changing an old officer mindset can be a very slow process.

But ah, Afghanistan. This was a time when the hills of broken rock were pocked by flowers and piles of PMN anti-personnel mines collected by the nomads to prevent their goats stepping on them. In the towns, the sun bleached earth roads merged into ochre clay buildings where deep grained grey-wooden doors opened into cool black shadows. No lights, not a single Coke sign. It could have been the 12th century if it were not for the strands of Christmas tinsel wrapped around the Kalashnikov barrels of the Taliban. I really liked Afghanistan and the Afghans. My only problem on that trip was when the Taliban stamps in every region ate the pages in my passport, obliging me to peel out a useful visa for Angola (always hard to come by). I met Faiz Paktian Mohammad in Islamabad that time - he was also concerned about Afghan deminer safety and coincidentally he had been the speaker who followed me at the Mine Ban convention in Ottawa.

Colonel George Zahaczewsky (Colonel Zee) had given a presentation after Faiz in Ottawa. He read a long paper intended to show that the U.S. government was spending vast sums on research to develop demining equipment as some kind of compensation for being unwilling to sign the Mine Ban Treaty. I caught up with him afterwards to ask how they could be spending so many millions on developing equipment for demining with nothing to show for it anywhere in the world? He said he would get back to me. The Ottawa conference venue was full of faces glowing with either self righteous excitement or professional anger. I listened to some of the two-dimensional rhetoric but there was no place for me so I slipped back through the snow to a distant hotel room wondering why I had agreed to give up a week for this.

Back in England a month later, Colonel Zee telephoned from the Pentagon to ask whether I would consider working with his US Army CECOM NVESD team. (CECOM NVESD is short for Communications and Electronics Command, Night Vision and Electronic Sensors Directorate, a title that justifies the acronym.) "What do you want me to do?" I asked suspiciously. "What do you want to do?" he replied.

So I took a contract with them as a "mine clearance subject matter specialist" with the money to rework my PPE designs and a remit to travel the demining world recording how people worked, gathering accident data, and testing their US designed equipment. In fact I declined to test most of the US designed equipment because it was inappropriate for use in humanitarian demining. An example was the quick-setting expanding foam used to spray over mines so that you could safely step on them after three minutes... And then how do I uncover the mine to destroy it? No answer. Another was the 32 ton Mine Clearance Cultivator, a massive bulldozer converted to push a plough that could lift large anti-tank mines to the surface. What about the smaller anti-personnel mines surrounding the anti-tank mines? And surely it must break itself every time the plough hits a tree root or unmovable rock as the machine pushes forward? "Oh it's only for anti-tank mines and it works fine in our test beds". What a pity that I have never seen a minefield that is a sifted sand-bed seeded with conveniently large mines. Colonel Zee was challenged by the need to spend money in states that supported his budget. He was also saddled with a bunch of engineer bureaucrats with zero knowledge of anything outside their bureaucracy. Beverly Briggs was his second in command and she was trying but when she died it was perhaps inevitable that it would fail. But I did take an air spade to test in Afghanistan - and just getting it to Kandahar was an achievement in itself.

Powered by a large compressor it was always going to be an unrealistic alternative to hand tools. It could have uncovered mines safely in most soil but not the hard packed loess clay out in Afghanistan which the air jet merely honeycombed with tiny air channels. Non-intuitively, the air jet could cut the ground and blow stones around but could not apply enough pressure on a mine to detonate it (I did try). Clever, but not exactly practical. Even if it had worked, the compressor could not be moved over rough ground and cost thousands of dollars. The hand tools the deminers used cost a few dollars and were easy to carry. I had only agreed to test it because I could not refuse to test everything - and because I liked the men who made it. Well, I could have been wrong, and just testing it ticked some boxes for my employer.

And I got to return to Angola, Mozambique and Cambodia plus visit Bosnia and Croatia, spending time in as many minefields as possible, learning from the deminers how they really worked and when I had their trust, I filmed them. The record was supposed to educate the people in Washington but that proved to be a little optimistic. The bureaucrats were not interested in the detail and ignored the work of this "alien" contractor. I regret that I was so busy learning and doing my own thing that I was of little use to Colonel Zee.

The Humanitarian Mine Action (HMA) years

In the late 1990s, the term ‘Humanitarian Mine Action’ (HMA) was adopted to describe activities in support of the Mine Ban Treaty. This roughly coincided with the time that I put PPE development aside and started to pay much more attention to other aspects of Humanitarian Mine Action. I had already worked as a deminer and surveyor, begun writing Standing Operating Procedures (SOPs) and training material and advised several research and development efforts but these things had either been done in support of my work on protective equipment or simply as favours to friends.

The internet was picking up speed and the Menschen gegen Minen (MgM) demining forum had more than 4000 subscribers – amazing at the time. This was the platform that got me known for questioning received wisdom at a time when things needed to change. The same was true of Hendrik Ehlers at MgM, but he was also an entertaining performer so he was in greater demand at the plethora of conference events held in the late ‘90s. The Berlin Wall was down and the new millennium was going to mark a new beginning in which there would be no place for wars and landmines. Many of us were swept up in a heady humanitarian enthusiasm that is hard to credit post 11th of September 2001.

This is me in Sweden in 2000 delivering a paper entitled ‘Something is Rotten in the State of Demining’ (yes, but Denmark is close to Sweden.) My 'heady enthusiasm' was always tempered by realism. What was ‘rotten’ was our lack of concern for the deminers and their safety.

I knew deminers who had died and others who had committed suicide after being maimed unnecessarily. Most of these people would not have been demining if it were not for us. They were being paid to pursue our post-conflict humanitarian priorities, not theirs, so if I might be able to do something to prevent their suffering being repeated, I felt obliged to try. This despite the fact that many actual deminers really did not care about their own safety. Deminers were all men in those days. Conflict survivors, they were mostly hard workers who were both uneducated and unsophisticated. Many never planned further ahead than the next promised payday. Some took risks willingly and parodied the worst of the ex-pat "heroes" around. Perhaps I was being paternal or patronising to think that they did not deserve to suffer unnecessarily? If so, I was not alone. I had already worked alongside many people who had been junior officers and who did their best to keep their deminers safe in impossible circumstances. Contradicting prejudice, I was most impressed by the South Africans and the East Germans. It is true that I always tried to see the best in everyone but I was only ever seriously wrong twice (both Western Europeans, sadly). I did not expect much of my fellow Brits but have sometimes been pleasantly surprised. One of them unwittingly made a huge difference to my entire approach to the emerging demining industry. I was an outsider trying to understand - so when it did not make sense, I thought the failing must be mine. Mark Buswell changed this in Angola in '97 by making one simple, common sense observation.

Me in Angola, still bearded from Afghanistan.

At that time, all the demining organisations claimed to clear to a depth of 30cms using metal-detectors and bayonets. Popular detectors could not find some of the small mines when they were on the ground surface, and none could find them deeper than 10cms underground. The bayonet blade was 15cm long and was pushed into the ground at 30 degrees to the ground surface. "Do the trigonometry", Buswell advised. We could not reliably search to 10cm so could not clear to 30cm except by digging away the entire ground surface, which I had never seen done at that time. Hardly rocket science, but it gave the lie to the public claims of every demining group in the world at the time and that gave me the confidence to doubt their increasingly absurd claims about the number of square metres that a deminer could reliably search and clear in a day. Without intending to, Mark had given me the confidence to speak out when the emperor had no clothes. I still meet Mark from time to time. In 2025 (still without having bothered to buy a masters degree) he is working in Ukraine after managing a large counter-IED programme in Syria.

In the late '90s at the new Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD), I was introduced to HALO Trust's new director Guy Willoughby. HALO's charismatic founder Colin Mitchell had died and Willoughby, his shadow, had taken over. Retired Brigadier Paddy Blagden pointed WIlloughby out saying, "You'll get along famously: he was a jockey you know”. Coincidentally, I had been an apprentice jockey as a boy, so I approached him thinking that we had something in common. I was not to know that in the vernacular of the British army a "jockey" is a slightly derogatory term used to describe members of the Household Cavalry. My approach was rudely rebuffed and he stamped off. No sense of humour, that man.

When the company making my designs of PPE in Zimbabwe offered to pay me a small percentage on each item sold, I refused without much thought because I was not doing the work to make money. But when I thought about it, there were several good reasons for refusing. First, if that company were paying me, they would not go their own way so the technology transfer would have failed. Second, If I took their money, I would feel disloyal to them when I encouraged others to set up production of my PPE designs elsewhere. And finally, when I argued publicly for PPE to be used, everyone would think that I was just saying it to make money. When I was later co-opted into helping draft the first International Mine Action Standards (IMAS) and was then elected to serve as an independent on the "Review Board" developing those standards, I had reason to be thankful for having no commercial links with any PPE manufacturers.

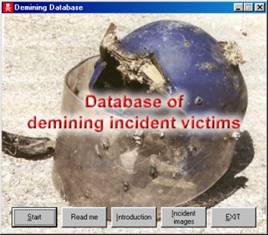

During the PPE work, I had started to collect accident investigation reports and laboriously enter them into a searchable bit of software which I designed and called the Database of Demining Incident Victims. I chose to call them "incidents" because some of the explosive injuries resulted from deliberate actions, so were not strictly "accidental". I collected hundreds of detailed reports and analysed them looking for causes that could be avoided in future and consequences that PPE might protect against. I was actually conducting formal Risk Management studies, looking for ways to avoid accidents or to reduce the injury that resulted but I did not know the language of risk management at the time. I thought that Risk Management was what stockbrokers did with investment capital, which it also is, of course. [See the Global SOP, Risk Management in HMA and the presentation Risk management in HMA organisations on the Powerpoint downloads page.]

There is rarely a single identifiable root-cause for any demining accident. They usually involve a combination of contributory failings that may be overlaid with bad luck or simple carelessness. When a deminer detonates a mine while digging it up (which is the most common activity at the time of an accident) he may have been working carelessly. There may also have been a failing of training or supervision, inadequate tools may have been provided, or there may have been pressure applied for the deminer to work too fast. Ignorance about the hazards being encountered was also common. When the deminers were not taught how the mines worked or what parts were particularly hazardous this was often because the person in charge did not know, so considered it unimportant. It is important for many reasons including the fact that some mines can be struck on the side with a tool without detonating while others are very likely to blow up in the deminer's face. The accident record made it very clear that ignorance was one of the causes of many entirely unnecessary accidents, perhaps exemplified by those times when fingers were lost as deminers tried to clean-out useful little aluminium tubes in their rest break (never having been told that they were detonators). A particularly arrogant ignorance was often also apparent at the highest level in the demining organisations. See the Accident case studies on the Powerpoint downloads page.

Ignorance usually played a part in civilian accidents too and the Mine Risk Education materials I had encountered around the world usually promoted fear, not knowledge. To tell a person not to go somewhere because it is dangerous when they must go there in order to get water, cooking wood or food is not helpful. People returning to a combat area usually know the difference between the threat posed by a mine and that posed by a dud mortar bomb. They do not need to be made afraid of everything. They need to be given all the available information about the hazards so that they can manage their risks more successfully. I think this is a respectful and sustainable approach to informing people about explosive hazards, but I know that it has offended some comfortably righteous Mine Risk Education professionals who are proud to know nothing about munitions whilst waving a pretty paper qualification.

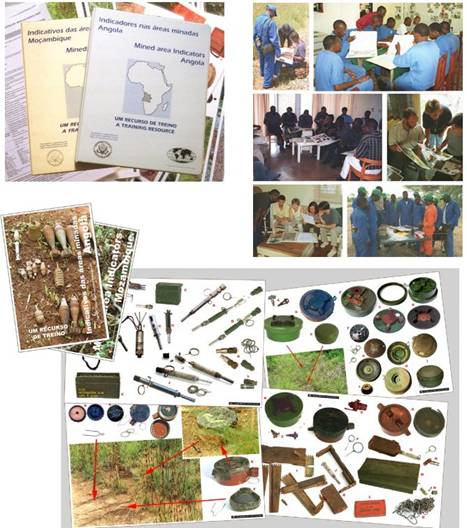

I decided to try to produce training material of use to deminers, civilians and other aid workers who were working in post-conflict areas. Rather than rely on sketchy cartoon drawings or photographs of munitions that had not been used (so bore little resemblance to the things that might be found) I planned to use detailed A3 photographs showing real hazards in the condition and context in which they might be found and to include relevant details of each hazard. The A3 sheets were laminated so that they could be passed around, studied and discussed. Given the varied hazards and contexts, different training materials had to be produced for each country and the text had to be translated. Because English is the language of demining, I put the text in parallel translation to help deminers learn the appropriate English term. I made a pilot set for Bosnia and, with help from Colin King, got in touch with the Golden West Humanitarian Foundation in America. They persuaded the US Department of State (DoS) to put up some money for me to produce separate 50 page training resources for Angola and then Mozambique. I spent some uncomfortable months travelling around in Angola to take photographs with no vehicle, very little money and speaking terrible Portuguese. Friends in the demining organisations MgM, NPA and HALO helped me. Angola was still on a war footing and more than once I was glad that my Portuguese was too poor for me to be mistaken for a spy. It was easier in Mozambique because I borrowed a vehicle, and because Mozambique, while sometimes a bit lawless, was genuinely at peace. The end results were printed up in America and looked good, so I planned to take dozens of the large loose-leaf folders to distribute around Angola and Mozambique before repeating the exercise in Cambodia and then Afghanistan. I spent a few days trialling them in Mozambique (shown below) but did not have multiple copies to distribute at that time.

The US Department of State (DoS) may always have linked humanitarian demining funding to covert surveillance, supporting those organisations that will work in areas of interest and report back dutifully. Friends working with a small demining company in the Balkans told me that this was happening in Bosnia where the American commercial organisation RONCO was getting contracts without going through the approved bidding process. I looked into it and something did seem to be amiss. RONCO had a very poor safety record and was taking work from small national NGOs, so I put a message on the MgM forum asking what the US DoS was doing – being careful to ask informed questions rather than accuse anyone of anything. My questions obviously hit the mark because I was summoned to give evidence to a Congressional Inquiry. Not being a US citizen, I was able to decline that invitation and so protect my sources. The man at DoS responsible for giving the dodgy contracts lost his job, and so did I. Golden West Humanitarian Foundation dropped me instantly. We had a "gentleman's agreement", not a formal contract, so I could not complain when they got Colin King to telephone and tell me that they were hiring someone else to distribute my training materials in Angola and Mozambique. The disgraced DoS man had been a friend of the HALO Trust director Guy Willoughby and, apparently enraged by my temerity, Guy Willoughby banned me from visiting any HALO minefield ever again (a ban that some of their better field staff have always simply ignored). Months later Golden West telephoned and asked me to suggest someone else for them to employ. I suggested the only American I knew who seemed to really understand humanitarian demining in the field. There was a nice irony in the fact that his experience had been gained working with a small NGO in Bosnia that had lost contracts to RONCO. A good man, he joined them and was still with them when last I heard.

Was I surprised by Golden West's reaction? Yes, because I still think that I was doing DoS a favour. Being so obvious is no way to run a covert information gathering exercise. Whatever, their support for favoured demining contractors, including the "Saintly" international NGO with an interest, has continued.

DoS later gave my training materials for use in Iraq, so providing Iraqis with photographs of mines that were not there and which were hidden in unfamiliar African bush and lush jungle. Well, I suppose that the gift ticked-a-box for someone. I produced half a dozen appropriate sheets for Iraq when I was there for the Manual Demining Study in 2003 (see Mined area indicators, Kurdistan/Iraq) but there is still a need for much more.

It seems that my training materials were never distributed in Mozambique because I was asked for them when I went there to conduct Manual Demining Trials several years later. All I could do was pass on the request and give the Mine Action Centre a digitised copy. The Angola training resource is on this site because it is still being used in Angola today. Everyone I ask finds it useful but I don't think this approach has ever been repeated in other countries so perhaps it is not as good as it looks, or perhaps it involves more work than people want to do.

The need for demining supervisors and managers to be appropriately trained before working in humanitarian demining had also been recognised by others. Donors objected to the fact that throughout the '90s, dozens of areas that had been searched by one demining organisation were searched again by another because the work had not been accurately mapped and recorded. Having a military background was no longer a sufficient qualification and the UN started expecting job applicants to also have a University degree. (For my views on the UN, click here.) It takes a lot longer to get a real degree than it takes to buy a Masters degree but obviously a Masters is better than a first degree, so the UN requirement was soon reduced to a "further degree". Respected Universities started offering fast Masters degrees in post conflict studies and related subjects to people with no first degree but with the money to pay. The better academic institutions made the students do some work (although not so much that they were obliged to give up their day jobs) and this did start to give graduates a shared vocabulary and some insight into the bigger picture of what HMA actually is (see Humanitarian Mine Action). The main downsides were that some graduates believed that their Masters meant that they knew everything they would ever need to know, and also the fact that the requirement excluded many good field people without the cash, confidence, skills, or the patience to engage in academic games.

Having lost my funding to complete the training materials, I had unexpected time in hand so I decided to have a go at building my ideal demining machine, something to cut undergrowth in front of deminers that was small enough to be transported in a pickup load-bay. US Army CECOM NVESD declared an interest but wanted to see a "proof of concept", so I went to Florida to build one with a Lockheed Martin friend (at my own expense, as usual). Using the diesel engine from a ride-on lawnmower, I got one made in his domestic garage while he worked on the remote controls. Panama City Florida is not the place to be welding, cutting and grinding in a closed garage without air-con.

My first attempt kind-of worked. The prototype wheels would have prevented shock transfer to the bearings but I knew that the bigger wheel rims would have been distorted by detonating any of the larger anti-personnel blast mines. Also, its limited engine size meant that it could not carry sufficiently heavy armour to reliably protect against bounding fragmentation mines and still have the power to work while climbing hills. Obviously I needed to rework it, but I ran out of money just as NVESD decided that they would not support its development after all. They were putting all their money into HSTAMIDS, a combination of the MineLab metal-detector and Ground Penetrating Radar, and into repeated work on the Tempest demining machine (which had been revised to try to meet impossible requirements and was embarrassingly useless).

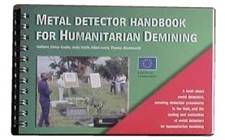

By that time I was heavily involved in drafting the International Mine Action Standards (IMAS) and had started work on the Metal-Detector Handbook for Humanitarian Demining. The book was Dieter Guelle's brainchild but he did not have the English to write it, so I did, also editing the contributions that Dieter drew in from academics at ISPRA. The race to replace the old Schiebel AN19 with a detector capable of finding the mines in electromagnetic soils had been running for several years. In fact, the patented MineLab technology in Australia had already won it but the European manufacturers were catching up and they wanted to be ready to cash in when NATO members started replacing old military detectors. For unexplained reasons, the Australian MineLab has often been sidelined despite the fact that the US army belatedly recognised its value. I suspect that a conservative military approach to design improvements coupled with brand loyalty explains the reluctance but all military kit is part of an arms industry in which heavy brown envelopes are said to have a powerful influence, so who knows?

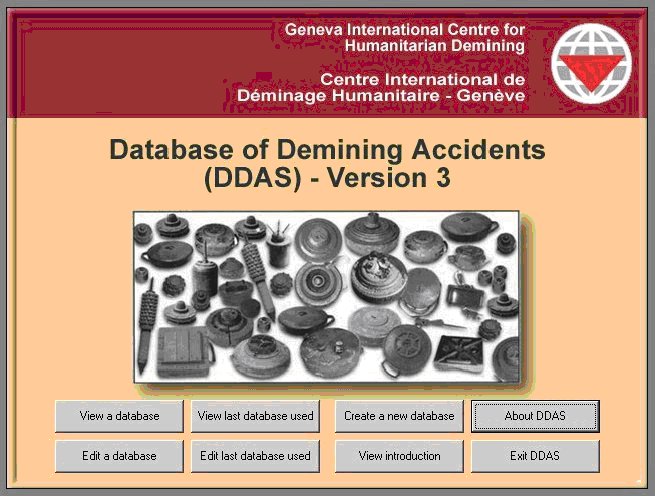

Working on the International Standards with the group that became the Standards Review Board, I frequently referred to the accident record. The better accident reports contained enough detail to provide proof of how the various demining organisations worked and were a source of hard evidence to the Review Board - which was a group of people who had little or no demining experience so clung to outdated military training. Not having a military background myself, my opinion was not valued unless I could back it up with hard evidence. The accident record was obviously useful but it scared the managers. What if someone were to publish their mistakes? What would the donors say? This has never happened because I have never published the names of the people or the demining organisations involved in accidents, but I understood their concerns. Accidents should be investigated and recorded in a professional way as they are in other industries. When the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) offered to take over my database of accidents/incidents and stop it being a one-man show, I agreed on the condition that they encouraged reporting and kept it up to date. The UK government put up some money and the Geneva International Centre renamed the database the Database of Demining AccidentS (DDAS) - a clumsy acronym imposed by the man who had been given the unenviable task of managing my work. I was contracted to design software improvements, manage their implementation and enter all new data. The contract included a requirement that I should stop gathering accident records myself because data gathering was to become GICHD's exclusive role.

By that time Colonel Zahaczewsky had helped establish an international test and evaluation capacity (ITEP) that would assess existing and new demining equipment without fear or favour. Independent academics would take over that side of things, which sounded very welcome. For a while, ITEP looked really good and it could have worked if the countries that joined had not allowed commercial self-interest to overrule honest objectivity. Its library of research efforts was a real asset that was effectively lost when ITEP closed down. I am told that it is on the Geneva International Centre's website but it is not readily accessible or searchable. I did hope that it would reappear in the James Madison University Data Repository but that is another hope that has been Trumped by today's techno-feudalism.

I built a mine dog training area in Angola for the German demining NGO MgM and set up another in Mozambique to assess the APOPO rats with help from a South African employed by MgM at the time. Most of the South Africans I have worked with had once been heroes of the old apartheid regime so were wary of the new Truth and Justice commission and liked to work outside South Africa. They knew the African context better than anyone and also managed deminers in the field better than others, so we always got along well enough. In Mozambique, despite our best efforts and endless patience, the rats were never ‘ready’ for testing (they constantly failed informal attempts) so the test area was finally 'cleared' of the 100 GYATA-64 mines we had gathered and placed at carefully measured depths in an artificially flat area free from vegetation. See APOPO rats.

Hans Georg Kruessen of MgM awarded me the "Don Quixote of Demining" award around then. (Yes, it is made from assault rifles.) Well, a German sense of humour, perhaps. Georg lived a hard and lonely life in the field for many years, punishing himself for something I never really understood. In 2015 he more or less died on the job from a cancer that he left far too late for treatment.

MgM's mine dog training area became the test area for a nuclear quadropole resonance method of detecting explosive vapour developed at L'ecole Polytechnique and I found myself taking my mine collection to Paris to help them. I was also in demand at Boston University in the States, and had already been a judge for a Canadian competition designed to get graduate engineers to produce demining innovations for several years. My limited success with PPE had not made me an "engineer" but it had reinforced my belief that there must one-day be technical advances that changed the face of demining. My ability to look critically at any suggestion was sometimes valued, and sometimes misunderstood. When a Danish group came up with the 'Purple Weed' or 'Red Plant' solution, I tried hard to see how it could be useful and decided that it might have a place in objective Quality Control - if it could work reliably. Because Quality Control is generally conducted after the area has had the undergrowth removed, been thoroughly searched and then declared clear, a low-cost way of checking whether any explosive hazards remained might have had value. I went to Namibia to conduct tests in the MgM mine dog training area. The plants should have grown red in the places where I had buried mines and raw explosives two years before. Unfortunately, the ARESA ‘Purple Weed’ System was a complete scam and I both wasted my time and fell out with MgM as a result. A Danish TV company (memorably named "'Bastard") had filmed the fiasco and interviewed me. They put together something that I was told had been edited to make Denmark look good and me look bad. Someone sent me a recording but I have never bothered to watch it. The media has always had its own agenda and headlines have always mattered more than facts.

There was a remote chance that some of the seed they had released during the trials had really been genetically modified. The seed was for a plant that was not native to the country (it was European watercress, seriously!) so I felt obliged to burn off the ground in the test area to kill any seed present after the ARESA people had left. I was doing that when I was asked to investigate a demining accident involving the Mine Clearance Cultivator, the 32 ton bulldozer converted to push a plough that US Army CECOM NVESD had spent years developing even after I had pointed out the flaws in its conception. The accident had occurred twenty miles away and I arrived at the site less than an hour after the machine had detonated an anti-tank mine. No one was hurt but the machine had been badly damaged and parts had landed in a nearby compound where people lived. I produced a pretty comprehensive report but NVESD complained that it included conclusions and recommendations. Apparently, in their system, it is not the investigator’s place to draw conclusions - which may explain why they had always been so slow to learn anything. Having conducted the investigation unpaid, the report belonged to me and there were lessons to be learned from it so I published it anyway. See the MCC accident report. This marked the end of any regular communication between myself and US Army CECOM NVESD.

Meantime, I was told that it was useful for the Geneva International Centre to get me involved in some projects because implicating me in a group decision would leave me obliged to accept the outcome without public criticism. Their insight into my sense of fair play was correct. One "working group" of which I was a voluntary member was intended to advise their "Manual Demining Study". Over two years it met twice (my travel costs paid) and as it was drawing to a close I asked, "So when will you actually start studying manual demining?" To date, their study had been an office based assessment of manual demining management activities. With little money left in the budget, they asked whether I could do a study of what deminers actually did?

With severely limited time and money, it would be a real challenge to do something professionally planned and executed, then ensure that independent witnesses were present to give the results maximum value. Fortunately I had friends around the world. I proposed to study different manual demining tools and procedures in four countries, conducting a formal time and motion study so that I could check the received wisdom over how much time deminers spent doing what. Then I would set up a disciplined test area and trial common tools and procedures to compare the strengths and weaknesses of each and assess them in terms of safety (the safety of both the deminers and of the people who would use the land). The people at the Geneva International Centre agreed.

The study of working deminers was never intended to give definitive results. I had done something similar around the world twice before and I knew that the varied hazards, climate, vegetation and ground conditions would make any attempt at direct comparison between them pointless, but I would also be timing the use of different procedures and tools which might lead to unanticipated, so useful, results. To go somewhere new, I got permission from a demining organisation in Iraq to spend time with them but that was when internationals were being taken for internet executions so the Geneva people told me not to go. Ever my own boss, I went despite the fact that the ludicrous cost of my insurance was far more than I earned. The late Mark Manning (murdered in England in 2014) was in the field with me there, as he had been in Angola long before. Mark was one of the no-bullshit originals who knew his hands-on stuff and really cared for his men but who would never have bothered to buy a Masters degree. More patronised than ever before (because I refused to carry a hand gun), I baked in the field and continued to learn.

I also went to Sri Lanka to assess the Rake Excavation and Detection System (REDS), to Cambodia to measure the advantages of using magnets and find out how much help it was to have heavy machinery removing undergrowth in front of the deminers, and to Mozambique to see their garden-spade based area-excavation system. As usual, in each case I learnt far more than I was expecting because I followed where the deminers were leading. Each place had its own personal challenges, the most disturbing of which was being unable to fly out of Iraq from Baghdad. The American army had introduced a visa system while I was working in Erbil, so I was arrested for not having one when I tried to leave. Finding armed American automatons pointing guns at me and not listening to a word I said made my blood run cold (an achievement in an Iraqi summer). I hate looking down gun barrels. Offering my cigarettes did not work so I shouted angrily until my raving attracted a senior officer who strolled over, rolled his eyes, sighed, and let me get on the plane, of course. No one noticed the "training aids" in my bag, but that was ever so. I had permission to hold parts of mines in Britain for training purposes (having permission is a Mine Ban Treaty requirement) and had brought many empty cases home for myself and others over the years. Knowing what you are looking for is, after all, rather basic. They were harmless but did not look it, so I was always ready to explain their presence in my bag. It says something for airport security that I have never had to.

I asked the UK research group QinetiQ and the German institute BAM to comment on the design of my comparative trials and then be present in Mozambique to monitor them and draw their own conclusions. BAM asked for additions and I complied. Both came to the trials hosted by the UN's 'Accelerated Demining Programme' in Mozambique at their own expense. The UN's supervisors and deminers also had their opinions recorded. Norwegian Peoples' Aid (NPA) in Sri Lanka sent Jan Erik Stoa to introduce their rake detection procedure and train the deminers before the trials. The deminers knew the other tools and procedures but had refresher or continuation training for each. The exception was an NPA Mozambique team who were to use the tools and procedure that they used every day. This was a mistake because they sent people who did not want to do anything at all. By contrast, every supervisor and deminer that the UN programme let me have was a hard working professional with a lot of experience. All trials require variables to be controlled but the qualities of the people involved can be impossible to predict and manage. The trials went well but the work involved in making the test lanes, concealing targets, getting people together and then managing the fairness and recording of every timed event was rather trying. I knew that something was wrong with me and later discovered that I had been having mini-strokes in every country since Iraq. At fifty I was already too old. But the results were useful - see Comparing manual demining methods.

Meanwhile, two years had passed and the Geneva International Centre had not gathered a single accident report. The database software had been revised and I could not earn any money because there had been no data to enter. I could not even let them know about the accident records that I had gathered as I travelled around because it was a breach of contract for me to have collected them. Their failure to do anything to collect records was blamed on the objections of a certain "Saintly" British NGO – anything for a quiet life in the Swiss mountains, it seems.

When I took back control of the accident database and carried on entering data as before, no one in Geneva argued. Subsequent events make it ironic that the computer software still bears a Geneva International Centre logo.

Noel Mulliner, then with the UN Mine Action Service and chairman of the International Standards Review Board, gave me letters of support for the database so that I could gather accident reports - but I rarely got them unless I went to ask for them myself. Mine Action Centres are always too busy to do anything unless you are smiling in their face. The demining organisations NPA and MAG were good about providing data for a while, but then MAG's Tim Carstairs got paranoid and MAG stopped (Rae McGrath had long been supplanted). Guy Willoughby of the saintly HALO agreed to let me have all their accident records if I first showed them what I already had. I compiled a subset of their records and sent it, and I got no data at all in return. By that time the HALO accident record looked appalling and I knew what Guy's attitude to me was, so that was no real surprise. I should say that what I saw of HALO's work in the field was usually as good as the others despite the organisation having a very poor reputation. Some of their field staff were among the best (and often moved on from HALO as quickly as they could). I wondered what their founder, Colin Mitchell, would have made of it? It was a shame to see a British organisation that had once been a leader lose its way when it was only half way around the course. Like many others, I blamed the jockey.

The tsunami in the Indian Ocean occurred a week before I arrived in Sri Lanka with a Norwegian Peoples' Aid (NPA) contract to help them get two Indian and one Sri Lankan NGO accredited to do demining work by the UN supported Mine Action Centre (MAC). The global response to the tsunami meant that every charitable organisation in the world seemed to be there, fighting between themselves and offering bribes to allow them to spend their money on something, anything. I was based in Vavuniya, about as far from the sea as it is possible to be on the island, and I arrived as NPA was recovering from having had their base and all their equipment erased by the wave. Fortunately their base had been closed for the Christmas holidays so they did not lose any staff. These were interesting times - especially as there was hope that facing a common disaster would help spur the peace process between the Tamil Tigers and the Lankan Government. Norway had brokered the ceasefire and was putting a lot of money into removing the mines as part of making the conditions ripe for peace. But turning a ceasefire into a peace treaty was not my concern, or not directly so. I had to work with the Indian NGOs and feared that the Indian army's trigger-happy behaviour when they had been sent to Sri Lanka as UN Peacekeepers would not have been forgotten. It had not, so while NPA were working on both sides of the line, I was with the Indians on the Government side, lifting mine-lines that swept across the land like flotsam tidemarks left as the fighting had surged back and forth. More than 90% of all the mines I ever saw in Sri Lanka had been laid by government forces. The Tamils made their own mines, now called IEDs, and used them relatively sparingly (they also lifted Government mines and used them again at times). For some images of Sri Lankan IEDs, see IEDS and Humanitarian Mine Action on the Powerpoint downloads page.

The Indian NGOs (named Horizon and Sarvatra) were both staffed by retired Indian army officers. The Lankan NGO was a tiny national effort that tucked under the wing of Sarvatra. They all needed some guidance in the transition between a military and a humanitarian approach but there was no good reason for them not to be allowed to work. I wrote them better SOPs than anyone else had and quickly got them accredited with the Mine Action Centre, then worked with them on improving their machines to get some of them accepted too. Tim Horner was with UNDP Lanka at the time and his intelligence made my life easier. I was there as both a trainer and a Technical Advisor who spent time with the deminers in the field monitoring their work and reining them in when their enthusiasm approached recklessness. They were great. We were all using the rake excavation and detection system (REDS) pioneered by Luke Atkinson and I designed improved rake-heads, then made them at the roadside in Vavuniya with Raju Pilau, a retired major, and Cris Chellingsworth, a British volunteer who just turned up wanting to be useful. See the developing safer hand-tools page.

It was while I was there that I first met a tiny gravel-voiced Italian woman who was travelling around trying to study demining. Emanuela Cepolina’s enthusiasm and commitment were admirable. As part of her PhD research she wanted to build a very small demining machine based on an Italian rotavator. She thought it could be remotely controlled to process the ground and clear mines and cost just a few thousand dollars. I patiently explained what clearance means and described how even a small blast mine would damage a tiny machine, then encouraged her to concentrate on devising blast resistant wheels and a tool to cut undergrowth. Later, I found myself appointed as the external examiner for her doctorate thesis. Of her three examiners, one had to be someone who knew demining and the thesis had to be presented in English. Emanuela had tried hard so I agreed to what was an unpaid chore. The university did provide me with a lovely place to stay in Genoa while I read and assessed several doctorate thesis, none of which were original or impressive. The students had paid. The students received their doctorates despite my assessments. My opinion of academic excellence sank still lower.

One of the Indian NGOs had invested in the new Schiebel ATMID detector before deploying and they wanted permission to use it. I could not allow that because it did not work well enough to find the mines at the required 10cm search depth. The deminers said that it did and the Schiebel sales material claimed great things, so I contacted the Schiebel offices to ask how to maximise performance and was advised (in writing) to bang the search-head on the ground to get a better depth. I still have that letter. Ignoring that advice, I set up a test area and asked the deminers to show me that they could search to depth adequately. With all the time in the world, they failed - which I had known would be the case because the detectors could not reliably signal on the target mines at 10cm distance in open air so would never do so when they were buried under soil. The tiny Sri Lankan NGO had half a dozen Minelab F3 detectors but the plastic plates designed to lock the search-head hinge had all been broken. Flopping search-heads are not much use so I emailed MineLab and had a dozen replacement parts delivered cost-free within a week. Thank you Hugh Graham from MineLab. We trialled the MineLab and it could find all the targets reliably at more than 10cm but the little NGO carried on using the rake procedure because they never had the money to buy batteries for the metal-detectors.

In all the places I have worked, I have never worked with deminers who worked harder or more willingly that those retired Indian army men, for whom anything was always possible. Two of them asked me to find them work as internationals, and I did. But I did warn them to be careful what they wished for. I worried that they would find it hard to fit in. Staying in touch, I saw their disciplined work ethic feed the prejudices of western racism in predictable ways. Politically correct but culturally ignorant women in HMA management despised their "obedience". Male European "colleagues" refused to live in the same accommodation and when I questioned this, I found that their adult presence caused resentment because they had no sense of humour. In fact, the Indians were bemused by the reliance of the others on excess alcohol and internet porn. I apologised to my Indian friends for the shameful lack of sophistication of my compatriots - and for getting them work with arrogant children. The apology was not worth much.

As an extra, I also found myself tasked with introducing the remotely controlled MV4 mini-flail to the Sri Lankan army. NPA had already given one to the Tamil Tigers so had to give one to the government forces. It arrived and when I started it up, it ran amok. A mini-flail that cannot be controlled really is a terrifying beast. The factory in Croatia sent someone to sort things out quickly (very impressive service) but I had gone home before it was discovered that there was nothing wrong with the machine. We were trying to use it too close to the army's main communications base and its radio control system worked reliably at a distance of a kilometre.

This was around the time that Keith Byng of ROMTECH died. A Rhodie bushman and an original founder of Minetech, Keith had been the first person to teach me a kind of demining, then drag me around surveying in Mozambique. I took my first mines apart under his direction – and will never forget cutting through the detonator of an M960 with a hacksaw. Whatever, he was a real field man who I admired immensely despite his old-school paternalistic Rhodie racism and his inability to admit ignorance when he did not know something. He died of cerebral malaria contracted while working in Congo. Explosive risks have only ever been the half of it.

It was tough in Lanka without a decent place to live. With no sea breeze, no air at all, the humidity and temperature at night reminded me of Luanda in Angola (one of Africa's armpits in more ways than one). The Danish Demining Group (DDG) let us share their comfortable house until I annoyed Samuel, the boy in charge, by answering his questions honestly (he is a man in Geneva now, still dishonest with himself). No matter, we moved into an oven overrun with cats until my declining health obliged me to take a room with an air-con in the not quite luxurious "Hotel Nelly Star". NPA did finally rent a well equipped house but by then I was too ill to extend my contract.

After an emergency arterial operation, I stopped smoking and thought I could just pretend nothing had happened. I presented at a research event in Berlin and was almost unable to return home. Noel Mulliner helped me through the airport. My batteries were flat. I stopped. Fortunately I had a home to go to and a long-suffering wife to put up with my bad tempered recovery.

Three months later I was offered a Chief Technical Advisor post and turned it down saying that I was not yet up to accepting full time work. Olive Group understood and put me on a retainer. I wrote preliminary SOPs for them and went to appraise a few commercial tasks, but I was not happy. They were not going anywhere quickly and I lacked the commercial zest that they needed to get going. They let me go, and even today I thank them because they helped me get my engine running again.

When the Swiss demining organization FSD offered me a six month contract to close down their operations in Sri Lanka, I accepted. Well, I had not actually managed a demining programme but closing one down cautiously should be easy enough and I knew a bit about Sri Lanka. The first thing I did on arrival was upset the man who appointed me by turning down a proposed visit to a Colombo brothel. The second thing I did was pay $1000 dollars of my own money to get the Tamil office manager, Dilushan, out of jail. Being a Tamil in Colombo at that time was not easy. With help from Dilushan and my national Operations Manager, Rochan Christy (now an international in Sudan), I managed to reboot the effort and get some more funding so that the programme ran for several more years. But I annoyed people by raising deminer salaries to $120 a month (yes a month, so not exactly generous) and driving Tamil deminers accidentally shot by nervous police to hospital in Colombo (being Tamils they would not have got through the checkpoints without my presence).

We were working on both sides of the line but by that time any real desire for the ceasefire had gone. Far from bringing them together, jealousies over the distribution of reconstruction money after the tsunami may have made things worse. In any case, the sound of the government's Stalin's Organ was a nightly disturbance alongside an occasional crump close at hand. The FSD field house had a concrete first-floor balcony and I remember crouching behind it nursing a warm vodka as the local police - after having been spooked by a mongoose, peacock, or possibly a Tamil infiltrator - emptied clip after clip firing blindly into the night. Flakes of concrete fell into my hair. Someone offered me a cigar and I accepted, so ending my non-smoking year. Well, perhaps everyone needs a vice.

Back in Colombo there was fighting on another front. Dr Kunasingham ran demining for the Lanka government - and he hated the affluent International NGOs with a malign passion. At first, my former association with the Indian NGOs meant that I was tolerated, but after a while he started to be abusive to me too. It was not personal - he was abusive to all of us (UN women worst of all). If it was water off a duck’s back to Judy Grayson, it was not to me. I was representing FSD so I dutifully turned the other cheek for longer than was reasonable before I wrote a formal complaint to the government in which I described his behaviour in detail and argued that it brought shame on them. Copies went to everyone I could think of. The government agreed and Dr Kunasingham was dismissed, later going off to join his offspring in Canada. The Indian NGO Sarvatra's leaders backed me up, but Kunasingham's successor was uncertain about me. FSD were similarly unsure. They waited until the last moment before offering to renew my contract, apparently presuming that I would accept gratefully two days before I was scheduled to leave. That was a little shabby so I would have declined even if I had not already accepted a UNDP Chief Technical Advisor's (CTA) job in Tajikistan.

The staff gave me a plaque which I am proud to have in my office today. It is hard to balance being both "boss" and "‘friend" because you have to take the trouble to genuinely know and respect the team but it is the only way I could get a real team spirit. I could not have played the mill-owner if I had tried - so my approach was just what came naturally. Nonetheless, I think it is the right approach to managing any humanitarian endeavour, if obviously not an option for some mindsets.

Sri Lanka had been my introduction to the problems of programme management and I learned a great deal, including lessons about my personal limitations (I was still an inadequate public speaker, for example). One of the few things that disappointed me was the unhelpful competition and point-scoring between International NGOs. This depends in part on personalities, of course, and competing for funds always risks being a sordid business, but the competition went some way to explaining why demining organisations have always been so unwilling to learn from each other. This was one of those cases when HALO's staff were among the best, incidentally, a complete change from the year before when their own deminers had attacked their offices and vehicles in Sri Lanka. If I was impressed by HALO’s recovery, there were things about FSD at the time that I thought were very wrong, but subsequent management revisions and their appointment of Tony Fish (now sadly no more) made me believe that FSD made real efforts to improve. It always comes down to the individuals that are put in place, not the mere fact of having a position filled.

I was not looking for a career so I rarely applied for work. My strengths and weaknesses were known and if people wanted me to work with them, they should let me know. In Tajikistan, I knew and respected the outgoing UNDP Chief Technical Advisor but I had to look in an atlas to be sure of Tajikistan's borders. Knowing Afghanistan from the '90s gave me only the vaguest idea what to expect. Apparently Tajikistan's Mine Action Centre needed someone with technical know-how. Having been asked, I dutifully applied, was interviewed and I took the six month contract offered. I knew that this would be a different world so I asked UNDP to give me some training covering their systems and public speaking. They agreed, but they lied. Despite repeated requests for training, advice and help, the only person who ever answered at all was my predecessor William Lawrence who had moved sideways into Afghan border management so was often around. William had written several of the best accident reports on record, incidentally, and I liked his Regimental Sergeant Major (RSM) sense of humour. I survived my six months at UNDP Tajikistan with the help of the RSM’s caustic wit.

Being with UNDP meant moving in unfamiliar circles - but I had been obliged to do the Embassy circuit in Sri Lanka so I was partly prepared. The ex-pats in Tajikistan were a very pleasant surprise. It was as if all of the intelligent odd-balls and minor embarrassments in the world had been sent there to keep them out of the way. This was a group that could have been made for me! With eccentric good humour they let me into their circle and I felt privileged to be there. But I had forgotten how to have fun and made little time for it (a minor regret). What I did do was clash with the national director of the Mine Action Centre. Profoundly ignorant, he was insisting that all areas recorded as hazardous in the original survey of the country had to be cleared. The country survey has been conducted without enough time or money - and whole mountains had been recorded as mined just because one person reported that they had seen something somewhere up there. But the national director would not allow areas to be reduced by technical survey, or simply crossed off the list because they should never have been recorded as hazardous in the first place. Worse, beaming with patronising patience he explained that we were a MINE action centre so we had no mandate to clear submunitions and mortar bombs and must leave them alone. I have known other national directors who were given the position as a sinecure that gave them a car and a salary, but they were usually bright enough to let their advisors get on with the job.

The UNDP Chief Technical Advisor (CTA) to a national Mine Action Centre (MAC) is not supposed to go into the field much. He is responsible for ensuring that the 'five pillars' of mine action as defined in the Ottawa Convention (Mine Ban Treaty) are being upheld. That is Mine Risk Education, Victim Assistance, Advocacy, Stockpile destruction, and Demining itself. In a well resourced MAC, the CTA will have the support of Technical Advisors who can keep an eye on each element. I was on my own, but I had some very good nationals. The Mine Risk Education aspect was run by Azamjon Salokhov (then working for the Red Crescent and later with OSCE in Ukraine) and he was intelligent, active and eager to innovate. The Victim Assistance element was fine, not that there were many genuine mine victims but there were plenty of people disabled by conflict. The Advocacy element was there and although the Tajik administration was not very likely to listen, they were allowed to speak. I was assured that stockpile destruction had already been completed and had no real reason to doubt it. But the rushed survey meant that the demining was far too slow and inefficient to keep the donors happy, giving me good reason to get out in the field and see for myself before making a plan. The MAC’s Operations Manager, Parviz Mavlonkulov, was a serving soldier so under many constraints but intelligent and eager to help. He was working as an international in Iraq when I last met him in 2018.

The mountaintops around town and villages in the mountains has all been defended in the civil war and many had been attacked using cluster bombs dropped by Uzbek planes flying on behalf of Government forces. Either the pilots did not understand the need to drop their bombs from a height great enough to allow the cluster bomb to burst and the submunitions to disperse, or the defending fire meant that their only concern was to drop them and get away. Either way, there were dozens of cluster bombs that had struck the ground intact, split open and were slowly spilling their submunitions down the mountains. These were old Soviet ShOAB 0.5 and AO 2.5 submunitions that were designed to be armed by spinning through the air and then detonated by the impact of landing. The only demining NGO working in Tajikistan had collected and destroyed hundreds of them during their previous work. When I went surveying I found them scattered over the sides of mountains and collecting in gullies so I went on to interview the local authorities, townspeople, rural health centres and remote households about their impact.

The only accidents anyone knew about had occurred when taking them apart, throwing them off cliffs or using them as fuel on shepherd's fires. Friends provided full details of their fuzes in Russian and English, confirming that these (even when armed) required a heavy impact to detonate (or the heat of a fire). The shepherds had seen soldiers burning chunks of high explosive to heat their mess-tins so they knew it would burn, they just did not know about the need to remove detonators.

When I returned to the office I found that there was no system in place to record new data despite the Geneva International Centre having provided expensive IMSMA map database training over several years, so my survey efforts could not be added to the database. My National Director did not agree that there was a need for it. In his eyes, my job was to get him lots of overseas trips to conferences about mines regardless of his inability to communicate. The translator explained privately that his salary was low and the allowances that the UN paid for travel meant that a few days away could more than triple his monthly income. I had to understand, he had daughters to marry off and weddings were expensive. The Campaign against Cluster Munitions (CCM) was gathering pace so I got submunition clearance onto his agenda by getting my National Director invited to a CCM conference in Europe - travel allowances paid by UNDP. Simple, if somewhat sordid.

Both the BBC and the CCM sent film crews and I showed them a few sites but the BBC’s locally hired cameraman let them down, and the CCM would not use their footage because I was picking up submunitions to show them that they were not de-facto landmines. Some types are, of course, but not these. Campaigners have never understood that blanket bans on munition types without regard to the threat presented by their varied fuze systems seems rather silly to those of us charged with finding and clearing them. The BBC broadcast a radio interview and although I was widely accused of sounding like a product of Sandhurst, my family liked it. Perhaps everyone’s self image dates from their youth. I still see myself as a country boy from Totnes in Devon even if I have mislaid my country accent along the way.

Half of my time was spent in the field (the mountains) and I really liked the place and the people. Every time I came back and put on my office suit, I found an inbox crammed with UN reporting requirements that no one had told me to expect. I was obliged to write fluff between stroking possible donors with credible lies. Well, I had staff relying on me to get their salaries funded… I started to understand why CTAs mostly sit at a desk and prefer not to know enough to know when they are lying.

Then there was a death - an entirely unnecessary demining accident that was partly my fault (by omission, at least). See Accident Case Study 1 at Powerpoint downloads. The investigation, conducted by William Lawrence and myself, found more failings than were credible but no one wanted to acknowledge any fault or correct error. The international demining NGO involved sent one their directors (a lawyer) to complain to the acting UN Resident Representative who told me to revise the conclusions of the investigation. He was sure I was right but I should "tone it down". I patiently explained that it already had been toned down. I had left out the fact that the demining organisation's manager had lied about his experience in his CV (he had none) and had obstructed the investigation at every turn. I had not mentioned that the ex-pat specialist who was supposed to be present at the time of the accident was drunk, and I had downplayed this man's failure to correct the absence of basic area-marking at other sites under his control. I had ignored the fact that the organisation was unable to provide any written SOPs at all, which I acknowledged was partly my fault because I had just presumed that they must have some. The UN interns serving as desk officers who were supposed to support my work found my discomfiture funny because the incompetent NGO manager was their drinking friend.

Well, it was funny. I am not cut out to be a UN lackey. (For my understanding of the UN involvement in mine action and an explanation of why I support it despite its failings, click here.) The discredited NGO manager (appropriately named 'Storey' because he certainly did tell stories) moved across the road to the offices of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) where he was appointed as their instant 'mine action expert'. He came to the Mine Action Centre and convinced my gullible National Director that OSCE would be a better partner than the UN by promising him more trips abroad with expenses, so my National Director told the UN that he did not need a Chief Technical Advisor anymore. I knew it was happening and did not argue. I did not want to be a part of any system that was this corrupt, incompetent and gleefully ignorant. The UN were happy not to renew my contract or replace me. Their timing was poor. I was halfway to getting Canadian funding for a national demining effort and had a really happy team of staff.

Not realising that UNDP had nothing to do with the UN Mine Action Service (UNMAS), my staff wrote to UNMAS asking for me to be retained. I was touched by that, but my departure did not really matter. Tajikistan's mine problem was so small that it would never have attracted international funding if there had not been a desire to have a stabilising presence on Afghanistan's Northern border. I got two of my staff into European Universities and supported others in their applications for international work. The best I could do.

As arranged with the international NGO's Director, the UN office waited until I was gone and then tasked others to rewrite my report of that accident. No one had told me and I first saw the rewrite in 2018 - when I was obliged to smile. Co-authored by a friend, the revised report looked different but drew exactly the same conclusions. Fortunately, the International NGO's head office was not entirely blind. They had a major restructuring and revision and even checked out whether I was available for work later, so there seem to be no hard feelings on their part. Demining is just a business to them.

Every year I had to find time to make my contribution to the International Standards review board. By that time there were more than 40 separate Standards and the more management experience I gained, the more convinced I became of the need to refine those Standards that I had not felt qualified to have an opinion about earlier. I was also more confident that there was a need to provide pragmatic guidance to the people actually working in the field. It was around this time that my contribution included writing a TNMA (Technical Note for Mine Action) covering "field risk assessment". I was also working every year to get the PPE requirements in the standards changed and to stop people using demining machines and calling the result 'clearance'. Clearance is defined in the standards as the removal of all explosive hazards to an agreed depth - and there is no demining machine that can do this. However, there has always been a powerful mechanical lobby – people making money out of these big and very expensive demining machines – who had friends at the Geneva International Centre. They could not answer my arguments but opposed me anyway. True, I know that winning an argument does not necessarily make me right, but I was right over this.

Norwegian Peoples' Aid (NPA) was setting up for clearing the Syrian border minefield in Jordan and I was asked to help out. I had been asked to go when they were clearing the border between Jordan and Israel but UNDP's Chief Technical Advisor in Jordan, Olaf Jorgensen (a Canadian), told them that I would not be acceptable. We had met ten years before in Mozambique at a conference when he was looking for a job and told me that there was money to be made by getting into demining management with the UN. I despised his motives but he was right. Without having ever seen a mine, he used his ability to charm, spin fluff and fill forms to get a lucrative position within the UN bureaucracy and a generous pension. The right kind of UNDP Chief Technical Advisor, perhaps, but I cannot help wishing that the word "technical" were omitted. When NPA replaced some staff, Olaf did not notice that I had been brought in until after I was already there. He pretended not to mind and I pretended not to know about his earlier objections. The man cannot help being the descendant of a telephone sanitiser.